News media

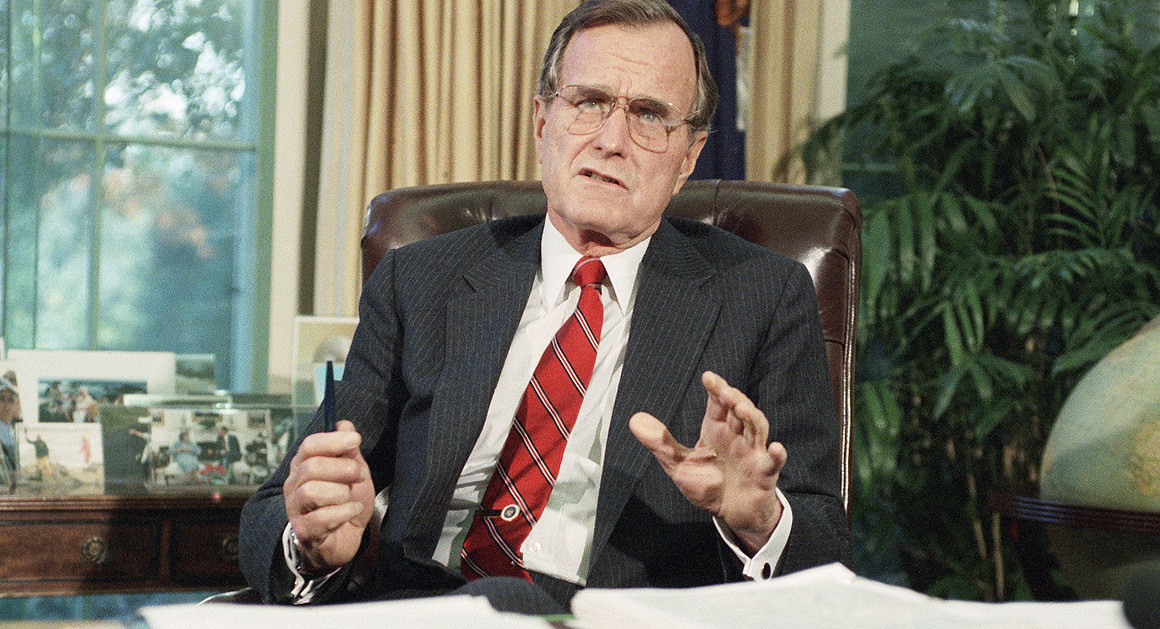

featured unstinting praise of the 41st U.S. president when

George Herbert Walker Bush departed at age 94 on November 30 at

his home in Houston. Five days later, when his memorial service

took place in Washington, DC, U.S. offices closed for a

“national day of mourning;” and for 30 days, official flags flew

at half-staff.

News media

featured unstinting praise of the 41st U.S. president when

George Herbert Walker Bush departed at age 94 on November 30 at

his home in Houston. Five days later, when his memorial service

took place in Washington, DC, U.S. offices closed for a

“national day of mourning;” and for 30 days, official flags flew

at half-staff.George Bush Sr. occupied the White House from 1989 to 1993, after serving as a U.S. representative, U.N. ambassador, CIA director, and vice-president.

Few individuals are all good or all bad. The credit side of the Bush ledger could include successful arms negotiations with two Russian leaders, work on environmental measures, and approval of legislation affecting civil rights (though rights legislation earlier drew his opposition). He took pride in his support for disabled persons and was concerned about education. Maybe add his words, “I want a kinder, gentler nation” (perhaps drowned out by his meaner, rougher actions).

The debit side takes in his pro-Vietnam War stand in Congress and his 1988 presidential election campaign against Michael Dukakis, notably the infamous Willie Horton ads and the empty vow, “Read my lips: No new taxes!” It might also include his messy performance at dinner with the Japanese prime minister. But those are mere bagatelles compared with the actions described below.

Onto the list goes his active support for Central American groups that Ronald Reagan called “freedom fighters” but opponents considered terrorists or murder squads. Then too, in attacking Panama in December 1989, he violated both the Constitution’s war-powers clause and treaties prohibiting aggression and foreign intervention. (It’s no excuse that all presidents since Truman—possibly excepting Carter—have done likewise.) The Constitution, Article VI, considers U.S. treaties to be federal laws.

The following August, without any enabling law, treaty, or agreement, Bush sent 200,000 troops to “defend Saudi Arabia” after Saddam Hussein’s takeover of Kuwait. A lawsuit by 54 congressmen charged that the president was hellbent for an illegal war with Iraq. The suit and widespread unease in Congress about his bypassing of the legislative branch prompted him to throw the war question into the hands of Congress, where it belonged under the Constitution.

Bush vigorously protested Iraq’s aggression—he called the Iraqi dictator, Saddam Hussein, “Hitler revisited”—oblivious to his own aggression, in Panama, not eight months earlier.

In narrowly approving the Persian Gulf War, Congress came closer to exercising its authority to declare war than on any other occasion since World War II. However, Bush et al. pressured Congress to vote aye and fed it deceitful, anti-Iraq propaganda. Moreover the massing in Saudi Arabia of battle-ready troops plus materiel (a doubling to 400,000 troops was announced right after election day) presented almost a fait accompli. There was to be limited use of force to expel Iraq from Kuwait. But like all modern wars, it produced atrocities and punished innocents.

Involved in Iran-Contra scandal

As vice-president under President Ronald Reagan during the Iran-Contra scandal, Bush attended most key briefings and meetings on Nicaragua that Reagan did, and must have known much of what Reagan knew.

So says a 2011 report, “Iran-Contra at 25,” from the National Security Archive of George Washington University. Its source, obtained in a Freedom of Information request, was the 1991 “Memoranda on Criminal Liability of Former President Reagan and of President Bush” by the office of Lawrence Walsh, independent counsel who investigated the scandal from 1987 to 1993.

The Reagan administration had secretly and illegally sold arms to Iran to finance the illegal support of the Contras, CIA-trained groups seeking to overthrow the leftist, Sandinista government of Nicaragua. The U.S. actions violated several statutes specifically banning Contra aid, limiting arms exports to defensive uses, requiring congressional approval, and so on.

While vice-president, Bush presided over the Special Situation Group, a high-level crisis-management committee, which in 1983 recommended specific covert operations in Nicaragua, including the mining of harbors and rivers. That year, as Bush presided, it also proposed an invasion of Grenada, Caribbean island nation with a population then a 2000th that of the U.S. Days later, without the OK of Congress, Reagan signed a paper approving the invasion.

Bush attended at least a dozen meetings at which illegal aid to the Contras was discussed between 1984 and 1986.

At a secret meeting of the National Security Planning Group, Bush and others discussed ways to maintain the Contras’ war despite increasing congressional opposition. They talked of asking third countries to fund and sustain the effort. Secretary of State George P. Shultz warned it would be an impeachable offense.

Bush countered, “How can anyone object to the U.S. encouraging third parties to provide help to the anti-Sandinistas? … If the United States were to promise to give these third parties something in return … some people could interpret this as some kind of exchange.” Yet Bush later arranged a quid pro quo deal with two Honduran presidents to allow the Contras to use Honduras as a base of operations against the Nicaraguan government. He also met with a high Israeli official to get help in selling arms to Iran.

The sale was meant to serve another purpose aside from finance: getting Iran’s help in securing the release of seven U.S. hostages being held in Lebanon. A 1986 entry in Bush’s diary said, about trading arms for hostages, “I’m one of the few people that know fully the details….” The existence of the diary came to light in 1992. The independent counsel’s office considered bringing charges against Bush for withholding the diary.

Neither Reagan nor Bush was prosecuted for Iran-Contra. Eleven Reagan officials were convicted in the scandal. But when Bush became president, he pardoned all eleven.

Congress allowed President Bush to send “humanitarian” aid to the Contras, rebels who displayed no humanitarian impulses when, critics charged, they shot, tortured, and mutilated civilians and burned homes, hospitals, and schools.

Why the invasion of Panama?

On Dec. 20, 1989, while western nations prepared to observe a holiday associated with peace and good will, Bush launched a little war on a nation with one-hundredth the U.S. population—apparently practicing for the big one to come thirteen months later.

A cold war with Panama had raged for a couple of years. The U.S. condemned General Manuel Noriega’s illicit rule. Panama protested alleged violations of the 1977 canal treaty. The U.S. imposed economic sanctions, increased its strength at Panama bases, and conducted military exercises there. Noriega bolstered Panama’s defenses, vowed to stay in charge, nullified a presidential election, and thwarted a coup attempt. In a resolution December 15, the National Assembly declared “a state of war” from U.S. “aggression against the people of Panama,” appointing Noriega “chief of government” to deal with it.

Anti-American sentiment boiled over. When a U.S. Marine was fatally shot and a U.S. Navy officer beaten, Bush attacked.

He never consulted with Congress, much less let it exercise its constitutional prerogative to decide whether to wage war. In an address, he said he had contacted congressional leaders and “informed them” of his decision. He gave these purposes: to restore democracy, save American lives, protect the Panama Canal, and prosecute Noriega in the U.S. for drug trafficking. None justified an invasion under international law. Anyway, were they Bush’s real motivations? No one knows for sure. Two contemporary New York Times stories and a later online Newsweek piece suggest personal motives:

White House advisers told Maureen Dowd that Bush had felt Noriega “was thumbing his nose at him” while press and Congress unfairly depicted him and team as lethargic and indecisive. The huge military action was based largely on Bush’s “visceral feelings about the Panamanian leader and a conviction that diplomatic means had been exhausted.”

The late R. W. Apple Jr., Times chief Washington correspondent, called shedding blood an initiation rite for modern presidents, to display power. Bush’s action had particular significance, Apple wrote, because as recently as a month back, Bush was widely criticized for supposed timidity. In Panama, he possessed “very few alternatives,” because “other methods had all failed to remove or isolate General Noriega.” Dowd and Apple did not question Bush’s supposed right to change a foreign government.

Peter Eisner, then Newsweek Latin-America correspondent, wrote of Noriega, upon his death, that he had earned the trust of the CIA and Bush, its director, 1976-77. On the CIA payroll while Panama’s leader, Noriega helped the U.S., e.g. avert war with Cuba by acting as a go-between with Fidel Castro. Noriega’s U.S. ties ended when he would not aid the Reagan-Bush fight against leftists in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, Eisner wrote. Failure to control Noriega sank Bush’s approval ratings and “made him look weak….” William Loeb, New Hampshire Union Leader publisher, called Bush “an incompetent wimp.” The word “wimp” was getting more popular when Bush attacked.

U.S. civilian and military officials saw “no justification for the invasion.” A top Drug Enforcement Administration official told Eisner “Noriega had helped prosecute the drug war and safeguard the lives of U.S. officials.” Before the invasion, an ex-CIA station chief in Panama said he could probably convince Noriega to give up power but was not allowed to try. As for the U.S. drug trafficking trial, Eisner doubted Noriega’s guilt. Prosecution witnesses were 26 convicted drug traffickers, offered soft plea bargains.

Later a Guardian article presented a different slant on Noriega, “the man who knew too much.” Simon Tisdall said the military action and the show trial that followed in Miami both aimed at silencing Noriega to conceal “nefarious U.S. behavior in Central America.” Bush was into “often illegal covert intervention in the civil wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua…. Noriega acted as an intermediary with the U.S.-backed contra rebels … and with the Salvadorian government and rebels.” So his detailed knowledge of CIA operations in the region was “highly compromising,” and he had got out of control.

Imposing ‘democracy’ at gunpoint

Contemporary TV largely acclaimed the successful military action against the “brutal, drug-dealing bully” (Ted Koppel, ABC) “at the top of the world’s drug thieves and scums” (Dan Rather, CBS). ABC reporters said they were cheered while riding in a military convoy. A CBS poll of Panamanians found four-fifths saying sí to the attack on their homeland. An NBC correspondent called OAS diplomats who condemned the invasion a “lynch mob.”

But New York’s Newsday told of residents cursing under their breaths, afraid to speak out, as U.S. soldiers searched a home. A few press reporters contacted hospitals, ambulance services, funeral homes, and human rights groups to tell of thousands of casualties and a legion of homeless people. The New York Times pictured a morgue filled with bodies of civilians killed in the attack. The Miami Herald reported anguish over hundreds of dead civilians buried in a mass grave: “Neighbors saw six U.S. truckloads bringing dozens of bodies,” and a mother cried, “Damn the Americans,” as her soldier son was buried. Some alleged that invaders targeted civilians and torched buildings.

Forty Americans died; 324 were wounded.

A CBS correspondent pronounced the invasion legal, “according to all the experts I talked to.” But whom did she talk to? Surely no one in the Organization of American States. Two excerpts from its charter follow.

“No State or group of States has the right to intervene directly or indirectly, for any reason whatever, in the internal or external affairs of any other State [Article 19]….

“The territory of a State is inviolable; it may not be the object, even temporarily, of military occupation or of other measures of force taken by another State, directly or indirectly, on any grounds whatever [Article 21].”

The U.S. was a party to the OAS Charter (since 1948); to the United Nations Charter (1945) and the Kellogg-Briand Peace Pact (1928), both prohibiting aggressive war; and to The Hague Convention on War on Land, banning bombardment of undefended communities or buildings (1907).

Noriega surrendered in two weeks. He served 17 years in prison in the U.S., then was imprisoned in France and finally in Panama, where he died at 83 in May 2017 following brain surgery.

Operation Just Cause, euphemism for the aggression, ended on January 31, 1990, after “neutralizing” (destroying) the Panama Defense Forces. By that operation, said Secretary of State James Baker, “the United States had demonstrated that it would stand up for democracy.”

U.S.-Iraq War I: limited slaughter

Reagan et al. helped Iraq when it attacked Iran. But when Iraq took over Kuwait and its oil fields in August 1990, the U.S. under Bush got the United Nations to condemn Iraq. Bush set about assembling a coalition to fight. He sent air and ground forces to Saudi Arabia, in response to a request from King Fahd, he said.

Bush consulted with twelve foreign leaders, like British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, but with no one in Congress (then in recess). Congressional leaders were simply notified of his decision, hours before the deployment to Arabia began. Resolutions supported his actions, but Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell (D-ME) said they were no blank check for war.

Secretary of State Baker claimed in Senate testimony that Bush could use the armed forces without congressional approval. Legislators of both parties expressed concern and wanted Bush to promise no war without congressional approval. Bush refused. He did not even inform Congress before publicly announcing the doubling of troops in Arabia. He lied to the press that he had consulted extensively with Congress. At a news conference, he claimed that it was the president’s responsibility, and his alone, to decide whether and when to wage war.

In Dellums v. Bush, 53 representatives and a senator sought to enjoin Bush from attacking Iraq without congressional authorization. The late U.S. Judge Harold H. Greene accepted the plaintiffs’ view that the Constitution’s Article I, Section 8, Clause 11 granted “to the Congress, and to it alone, the authority to declare war” (quoting Greene), witness the framers’ comments that it was “unwise to entrust the momentous power to involve the nation in a war to the President alone.” But he found the case not yet “ripe” because plaintiffs lacked a majority of Congress and war was uncertain.

Without conceding the constitutional principle, Bush decided a congressional resolution backing the UN’s stand could be politically helpful. He asked Congress to approve force unless Iraq left Kuwait in one week An opposing resolution would try sanctions instead.

At hearings, “witnesses” lied about Iraqi “atrocities.” Hill & Knowlton, a public relations company hired to promote war, had coached them. A Kuwaiti girl named Nayirah—later exposed as a member of the royal family and daughter of Kuwait’s ambassador to the U.S.—tearfully but falsely said she saw Iraqi soldiers fatally pull babies from incubators.

In the House, 268 members spoke; in the Senate, 93 spoke. The vote, on Jan. 12, 1991, was 250 to 183 for each resolution in the House, while the Senate voted 52 to 47 for force. The president first had to affirm efforts at diplomatic or other peaceful settlement.

Relentless bombing of urban areas for six weeks and the massacre of tens of thousands of Iraqi soldiers withdrawing from Kuwait on what has been called the “Highway of Death” went far beyond both the bounds of international law and the mandate of Congress: to get the Iraqis to withdraw from Kuwait.

At least Bush did not accommodate the neocons who urged total conquest and regime change. (Some say he held back at the behest of his Saudi friends, who favored rule by anti-Iranian Saddam.) That would be the handiwork of son George W., whom he strived to put in the White House following Bill Clinton’s terms. Yet the limited war left Iraq in ruins and probably cost the lives of more than 100,000 Iraqi soldiers and civilians. About 700,000 coalition troops participated, 540,000 of them American. U.S. deaths totaled 299.

Tens of thousands of Iraqi civilians may have succumbed, mostly from disease and lack of medical care, adequate food, and clean water, wrote Rick Atkinson, a Washington Post reporter, in the 1993 book Crusade: The Untold Story of the Persian Gulf War. (Some place the toll above a half-million.) Atkinson said the allies dropped 227,000 bombs, 93 percent “dumb” (unguided) and missing three out of four targets,

Among examples of inaccuracy: In Najav, bombs damaged 50 houses; in one, reporters said, 13 of 14 family members died. In Al Dour, 23 houses were flattened, and a woman sobbed that her three brothers, their wives, and eight children were killed. An “errant” attack on a bridge in Nasiriyah, killed 50. In Basrah, the Ma’quil neighborhood was bombed three times with a death toll of 125; and 70 died in two other neighborhoods. Bombs striking a hospital “inadvertently” killed four near Kuwait City.

Bush described the bombings as “fantastically accurate” in a war fought with “high technology.”

The author commented: “The sanitary conflict depicted by Bush and his commanders, though of a piece with similar exaggerations in previous wars, was a lie. It further dehumanized the suffering of innocents and planted in the American psyche the unfortunate notion that war could be waged without blood, gore, screaming children, and sobbing mothers.”

These were no accidents: air raids on food warehouses in several cities; on a large factory in Baghdad that allies said made biological weapons but Iraqis said made infant formula; and on the telephone exchange in Diwaniyah, killing 15 in a hotel and apartments that were adjacent.

“Smart bombs” proved no more humane than “dumb” ones. At least 408 civilians died in a Baghdad air raid shelter from two guided bombs. The U.S. military knew the shelter from the Iran-Iraq war but claimed it had a military function. Add that war crime to the big list of hits on homes, hospitals, and vital facilities.

Dirty tricks, coverups, shady deals?

Lamar Waldron, historian and author, made some little-known accusations on Thom Hartmann’s syndicated radio talk show of December 7. Waldron charged that Bush:

— Handled dirty tricks for President Nixon in Watergate days.

— As CIA director, covered up the crime of assets who blew up a Jamaica-bound Cabana airliner in 1976, killing 73 people.

— Also covered up the guilt of a CIA asset in the Florida murder of Johnny Roselli, who had been hired to assassinate Castro.

— Lived off the proceeds of Nazi slave labor, inherited from his father, Prescott Bush, using the money to go into business with the family of Osama bin Laden.

— Assisted his son George W’s presidential campaign through racially charged dirty tricks against John McCain in South Carolina.

— Helped Reagan cut a deal with Iran to delay the freeing of hostages until Reagan took over the presidency from President Carter.

— Evidently was in charge of deals with the Contras, a k a Nicaraguan death squads.

Greg Palast, independent journalist and author, writes of Bush’s connection with a Canadian-American gold mining company and a fatal incident that occurred in the 1990s, following his term as president. The company took over a huge gold field in Tanzania upon the bulldozing of thousands of small mines. Some 50 miners were thereupon buried alive.

Defamation of a vegetable (Bush publicly avowed his dislike of broccoli) is scarcely in the category of those other alleged offenses, but let’s end on a lighter note.

Bush, an oil man, gave as one rationale for war with Iraq: preventing Saddam from controlling the world’s oil supply. Kuwait was rich in petroleum, and during the crisis some cynic circulated a bumper sticker asking, “What if Kuwait’s main product were broccoli?” The late columnist Herb Caen ran my answer in the San Francisco Chronicle: “It wouldn’t make any difference. Bush hates broccoli and loves war.”